How does science tell us what the world is really like? It’s a question that Andrew Pickering, a theoretical physicist turned historian of science asks in his book The Cybernetic Brain. Through a look at the early history of cybernetics — the study of regulatory systems — he helps us think about how science guides us to see the world, often through different, conflicting paths. I had the pleasure of visiting him where he works at the University of Essex, and some excerpts from our discussion as well as one of his recent talks, which he gave at Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in Germany, follow.

While studying particles, quarks, and strings, Pickering learned to expect certain things of the world. Physics taught him that the environment we wake up to each day is a fixed and knowable place, with properties that can be studied and described. But over the years, he started to look at the history of what he was thinking about instead of theorizing it directly himself. He discovered that words like ”fixed” and ”knowable” belonged with other adjectives like ”young” or ”simple” when describing what the world is like; all are totally useless for the task.

Pickering says, ”If you look in the laboratory, a different picture appears. The world isn’t fixed. It’s lively and emergent, always surprising to the scientists themselves. The scientists continually react on the fly to what the world – in the shape of their machines, instruments, experimental set-ups – does, and the world acts back, and the scientists react to that, and so on.”

Pickering calls this waltz between matter, people, animals, and machines — which fizzle and burp and beep in unpredictable ways — the dance of agency. It shows us that science and scientists aren’t apart from or above the objects they study, nor the tools they study them with. They are always inextricably intertwined. Scientists act on the world, and the world acts back on them. But it is not a simple call and response. Each interaction causes new identities to emerge through an open-ended process of becoming.

Pickering: For the last 400 years, the standard way of thinking about the world and the West has been to think in terms of a clear difference between people and things. One way of thinking about that difference is in terms of agency. A conventional thing to say is that people are the only genuine agents in the world, but that nature, animals, and machines don’t have agency in any real sense. They’re passive, machine-like, and predictable. So that’s the basic view of modernity: on the one hand are human agents, on the other lies all sorts of predictable machines.

This sounds rather philosophical, but it also has practical connections. It is not just that people and things are different within the Western Modern imagination, but there’s a kind of asymmetry. We have agency and the rest of the world doesn’t, which means that in some sense that we are in control of the world, and in control of things. We treat the world as though it is standing around, waiting for us to take advantage of it.

Pickering writes in The Cybernetic Brain about how this self-serving form of Western scientific thought was challenged by the science of cybernetics. Many historians of science will trace cybernetics back to the work of Norbert Weiner, a mathemetician at MIT who came up with an anti-aircraft predicting device during World War II. But Pickering does not attribute the heart of the field’s inception to the military.

Pickering: If you look at most of the people who were involved in the creation of cybernetics, Weiner looks like an exception. Most of the people who were centrally involved were actually brain scientists, psychiatrists, people like that. So cybernetics grew out of, in my opinion, an unusual way of thinking about the brain.

The conventional way of thinking about the brain is as an organ of cognition. The brain is something that thinks and knows and reasons. A question would be, how do you model a brain on a computer that wins at chess? But my cyberneticians didn’t think of the brain like that. They didn’t think of it being a kind of cognitive organ. They thought of it as a performative thing.

Performativity implies being able to react to the environment at hand. When a performer goes on stage in front of an excited audience and takes in their energy, the show is going to feel different than that gig they played to an empty dive bar one summer earlier. The show changes because our brains react differently in each new dance of agency. We do not reproduce programmable outcomes, time and time again.

Pickering: If we understand that, then I can say what made cybernetics special as a science is that it recognizes that people are indeed agents, we do things in the world, but everything else has agency too: nature, machines, animals. So instead of having a kind of asymmetric dualism, cybernetics kind of levelled the ontological playing field between people and things.

Sometimes cyberneticians made machines that paint a picture of that point. The British cybernetician Gordon Pask invented the so-called Musicolour Machine in 1952. This was a musical instrument that turned light into sound, and in doing so, staged a dance of agency between the machine and the human that played it. The machine would respond to what the performer was doing, and could become “bored” if the human played it in a repetitive fashion. The bored Musicolour Machine would then refuse to respond predictably, forcing the human to try something new. Back and forth, the machine and performer would push each other’s buttons, caught up in an unpredictable performance.

Picking: And beyond that, the branch of cybernetics that has always interested me, insists that agency, powers, capacities, behaviours, these things are not fixed, they are emergent. We don’t know what the world is going to do until we act on it. We are continually finding out and being surprised by what the world will do. And we are coupled to nature reciprocally in this back and forth of human and non-human agency.

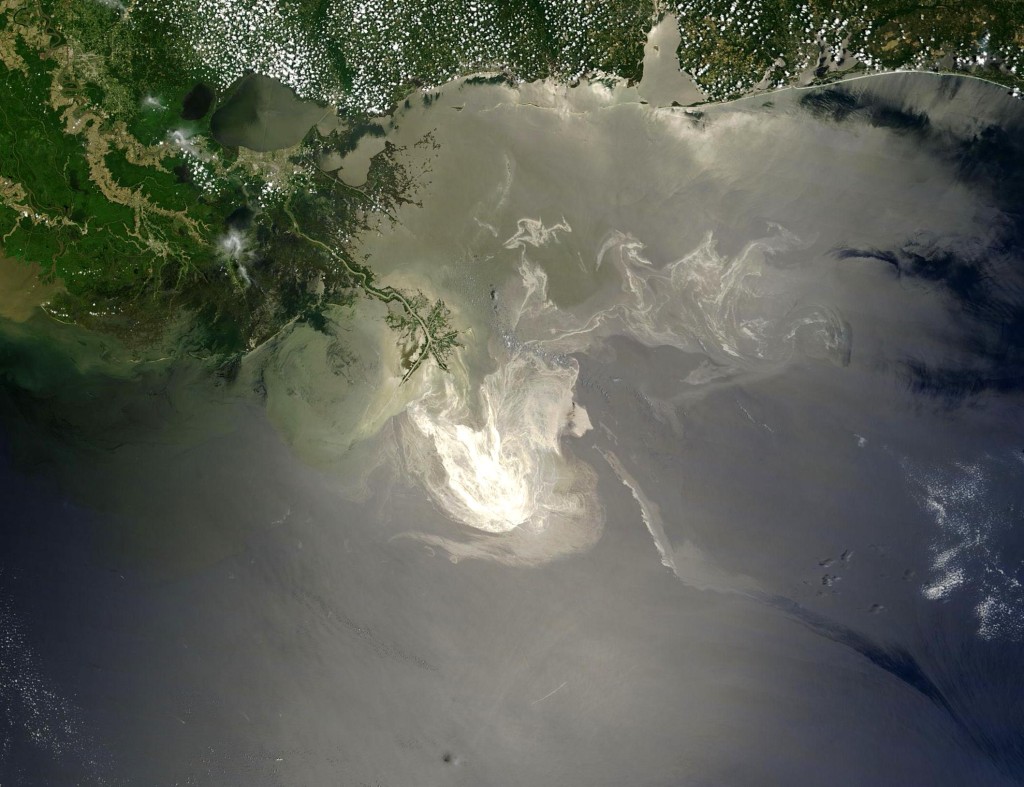

Think of your favourite environmental disaster, right? It’s an example of thinking that we can dominate the planet. I got hung up on the Deepwater Horizon disaster when they were drilling for oil in the Gulf of Mexico and it spilled for 87 days in 2010. Does it make sense to think that we can drill for oil a mile below the surface of the sea and control that? I think the answer has to be no. There might have been a few engineering mistakes, as one would say, but we should expect things to go wrong, and the more and more desperate we become in trying to dominate the planet, the more dangerous these things become. The desperate hope then is, that if people could get the hang of the idea that the world isn’t fixed and controllable, that it isn’t the way we’re taught it is from the age of around five onwards, then people would say, hang on, you know, this is probably not a good idea to do this. These mega-engineering projects are bad. Not in any specific way but because nature is emergent. Things are going to surprise us.

But there are fissures in this theory; grooves that bend it out of whack. After all, we have functioning industries that rely on wrangling nature into shapes of our own design. We have the chemical industry for example, and all sorts of biotech. One area that looms large is synthetic biology. Here engineers try to model organisms into “living machines” with novel biological processes that can help “heal us, fuel us, and feed us.” So, how should we make sense of this unpredictable emergence when nature doesn’t always disobey our commands?

Pickering: It’s true that we do seem to be able to, as it were, grab nature by the throat sometimes and make it do what we want it to do. We can do that kind of thing. But the point about emergence and being surprised by things is that when we grab nature by the throat in one place, emergence tends to burst forth in another place as bad surprises – things that we did not predict. One classic example of that would have to be global warming, wouldn’t it? On the one hand, we manage to extract coal and oil from the Earth, we turn it into energy and all sorts of other things. We seem to have a kind of mastery over nature in that respect. But then what finally dawns on us is that there’s a bit of nature that has escaped our control here. Carbon dioxide changes the planetary atmosphere, and results in global warming. There’s a bit of nature that we didn’t think about that is coming back to haunt us and produce potentially devastating effects.

Another angle on this is that if you look at these non-dualist, marginal traditions in the history of the West, including cybernetics, there seem to be very strong echoes of the East in them. So my cyberneticians, if you look at their writings and their notebooks, were all extremely interested in Eastern philosophy and spirituality. The resonances are not a kind of Cartesian Western philosophy that guides Modern Science, but Buddhism. You could say that the dualist modernist paradigm makes a clean split between science, religion, and spirituality, whereas these non-dualist traditions, just because they connect people and things and the cosmos together, have a kind of natural affinity to, not the West, but the East.

To root this a little deeper, Pickering tells us to think about bonsai trees. The shapes of these tiny marvels from the East are made from continual negotiations between the plant and the human who prunes it. The plant spontaneously sprouts a branch, then the human makes a cut, another sprouts, then is trimmed, sprout, trim and so on. In contrast, its Western counterpart of extreme tree-art can be seen in the Versailles’ Topiary. These geometric souls are fastidiously sculpted back into shape wherever they wander from form. So while the trees in Versailles are dominated and still, the bonsai inhabit an ontological theatre where they’re caught in the dance of agency with their human dance partner.

Pickering: We are taught, as we grow up, that the world is a knowable and controllable place, and we act that out. We tell our children the Earth goes round the sun like clockwork, and we invent all these clockwork mechanisms to explain it. But it seems to me that we act it out in more and more desperate ways, which somehow become more and more dangerous.

You know, the idea that we can march around the world, invading other countries, make them democratic, and turn them into what we want them to be, is also a mistake. And it’s not just a mistake in political terms. It is also an ontological mistake. We cannot reconfigure other nations any more than we can willy nilly reconfigure the planet in a material sense.

So the argument I’m trying to make is not an ethical one in that traditional sense. It’s not so much an argument about how it will be good to behave from a human point of view, it is a question of what the world is like, right? Western science has been elaborating this picture of a knowable, controllable world. Galileo, Newton, Einstein, that’s what they did. They did some beautiful and important work, it is totally admirable. On the other hand, I think it is totally misleading.

“Would I be different now if I’d grown up in a world of Musicolour machines, electrochemical paintings that keep evolving, rocks instead of crucifixes and meditation breaks instead of cricket and rugby? Yes! Yes, I would have been different.”

Considering how you were raised, would you be different too?