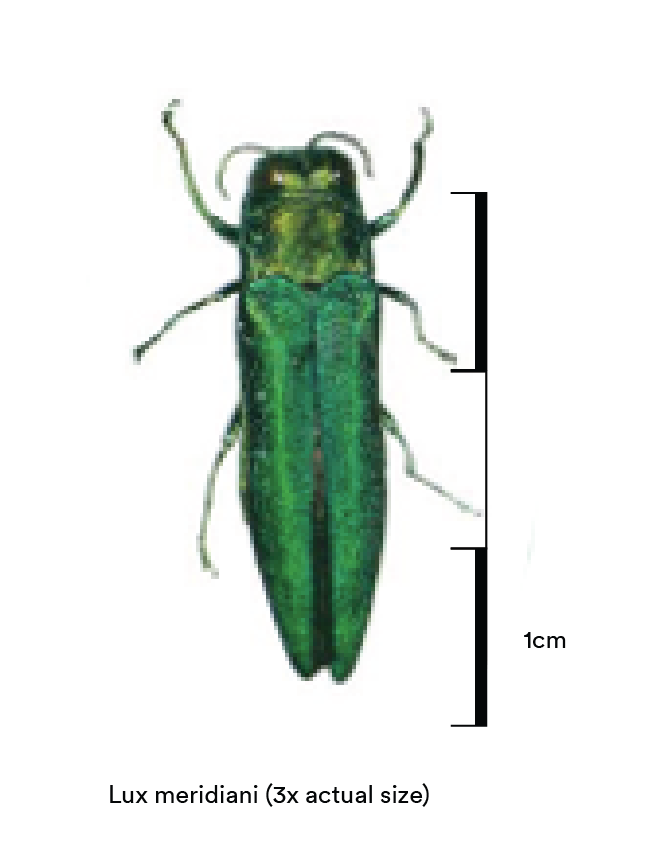

Lux meridiani is a small beetle native to East Asia that ranges from three to five centimeters in length. The insect has an expansive habitat and feeds on the leaves of Fabaceae (legume) family of trees. Its adaptability to temperature and weather, as well as its wide feeding range, allows it to proliferate in large portions of the world.

One of L. meridiani‘s key characteristics is a glowing abdominal light, used as a signaling mechanism during mate selection. Casually referred to as Lux due to this light, the glow of a single Lux beetle is the equivalent of a 1 watt LED light. The active chemical compound that produces this glow is luciferase, the same chemical active in glowworms and fireflies.

Starting at the larval stage of the beetle’s year-long life cycle, Lux emits a startlingly bright. Its relatively long lifespan allows it to reproduce in large populations, as it will lay eggs twice: during both the spring and the fall.

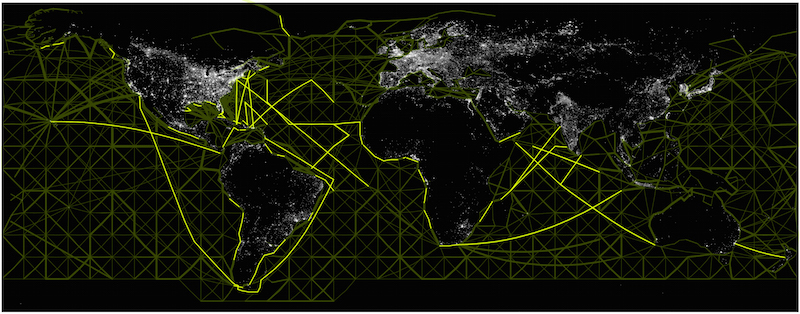

Brought to North American urban areas on wood pallets (presumably made from Fabaceae trees) via large cargo ships and then transported to major cities via an extensive freight truck network, Lux beetles have established a strong ecological niche in cities. Attracted to the heat of urban incandescent lighting, their population has gone unchecked by predators, aided by vociferous reproduction rates. As they do not directly damage trees or other property, their presence in cities tends to be perceived as more of a nuisance than cause for alarm. In 2018, there were an estimated eight billion Lux beetles in the New York Tri-State area alone (roughly half the number of ants in the region circa 2014).

System Disturbance

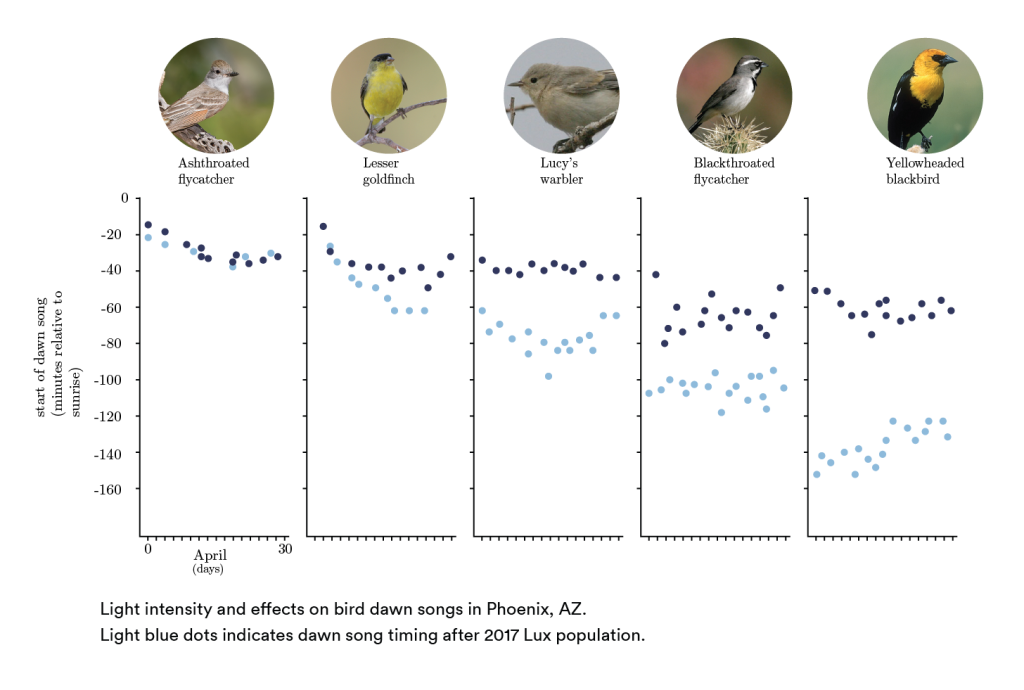

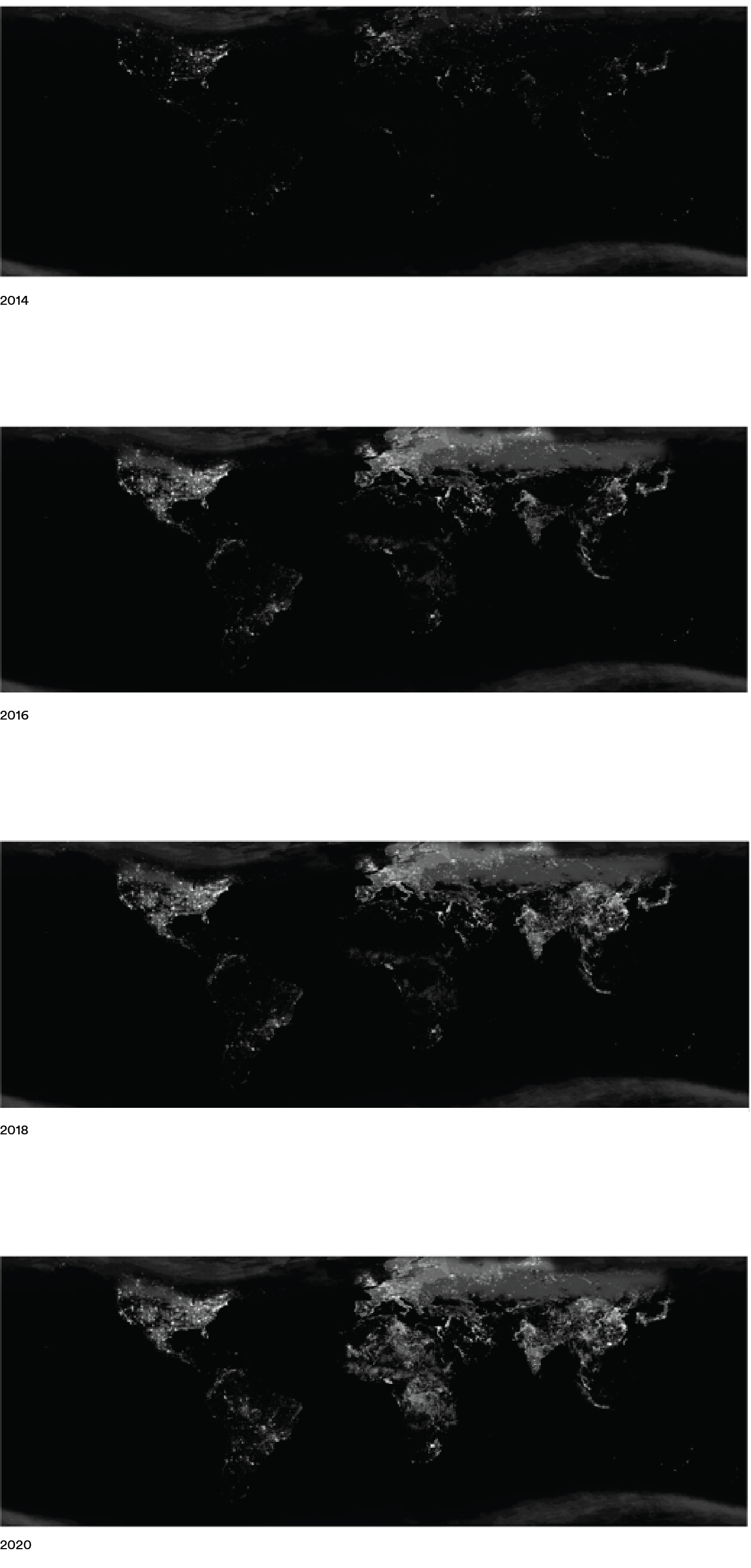

Lux has been the catalyst for an immense amount of ecological disturbance. The effects of its “persistent radiance” has created a waterfall effect on urban growth, agriculture, and ecosystem balance.

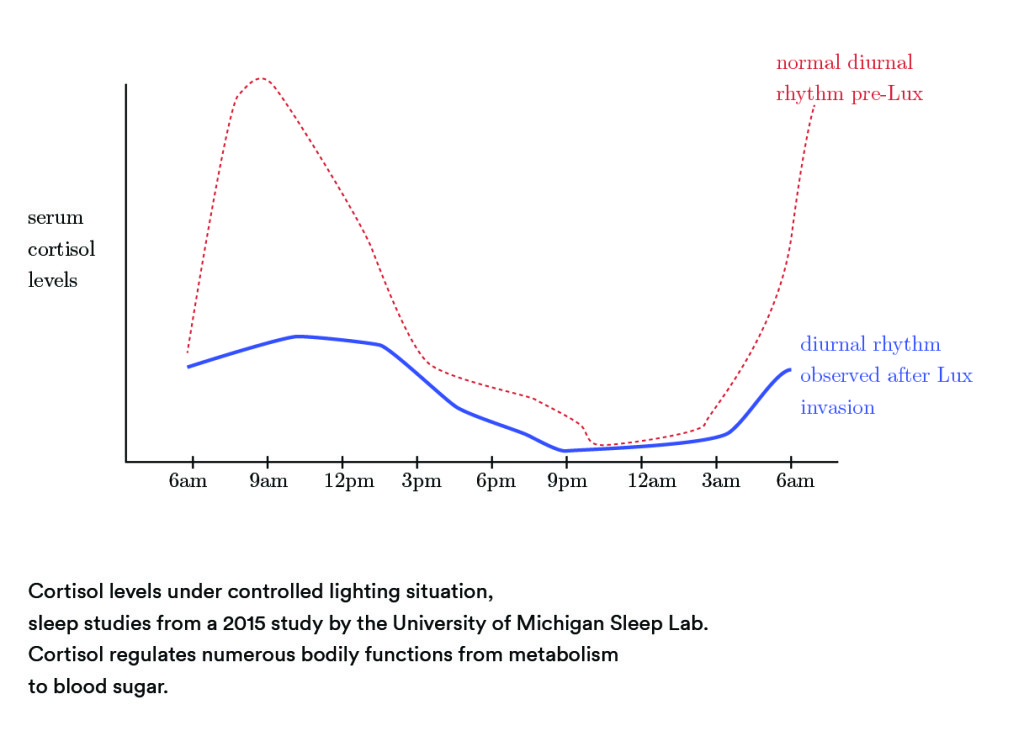

Persistent radiance has disrupted the circadian rhythms and diurnal cycles of countless plants and animals, in turn affecting everything from crop pollination to work and sleep schedules. Human insomnia has increased drastically in urban environments. Enabled by adaptive sleep cycles, large portions of the population have used these extra waking hours for work, generating remarkable economic growth for cities. This in turn fostered further urban expansion, creating more hospitable habitats for Lux, and accelerating a relentless feedback loop of light, productivity, and urban development. Economist Paul Krugman has remarked that Lux is the best thing to happen to city economies since electrical lighting.

Disruption in non-human species however, has wreaked havoc on agriculture and arable land availability. Loss of crop pollinators created an uphill battle remedied with genetic modification and artificial pollination. Common grasses and small flowers have disappeared rapidly without pollination, blowing valuable topsoil away and creating large patches of desertified, unfarmable land. In 2020, Congressman Rand Paul stated that if the US did not act soon, it would witness a disaster “worse than the Dust Bowl.”

But as in most ecological disasters, there is usually a silver lining. As the desert took over large amounts of previously arable land, desert species such as the Ash-Throated Flycatcher, the Spiny Lizard, and the Desert Tortoise began making these new arid lands their home. They became natural predators of Lux, due to excellent light detection developed during years in the desert acclimating to true nighttime darkness.

Food Security = National Security

The urban explosion and subsequent urban population boom additionally created high demand for food. In 2025, food security was deemed a major national security issue in the United States. Flower-bearing crops from apples to almonds became endangered as the population sizes of cities surged. In response, the United States Department of Agriculture, the Department of Defense, and the Department of Homeland Security proposed the “Total Ecological Food Security Defense Act.”

The bill proposed governmental regulation of publicly available seed types, mandated crop types to be planted, and declared minimum viable yields. Congress quickly ratified this bill and its effects were immediate. Farmers were mandated to focus their energy on growing genetically modified staple crops (wheat, corn, barley, soybeans) that could function without pollination, and the farming of water thirsty flowering crops such as apples and berries was banned. Manufactured, synthetic foods also aided in the nation’s fight for food security, and by 2027, the Department of Homeland Security declared the war on food scarcity officially “over.”

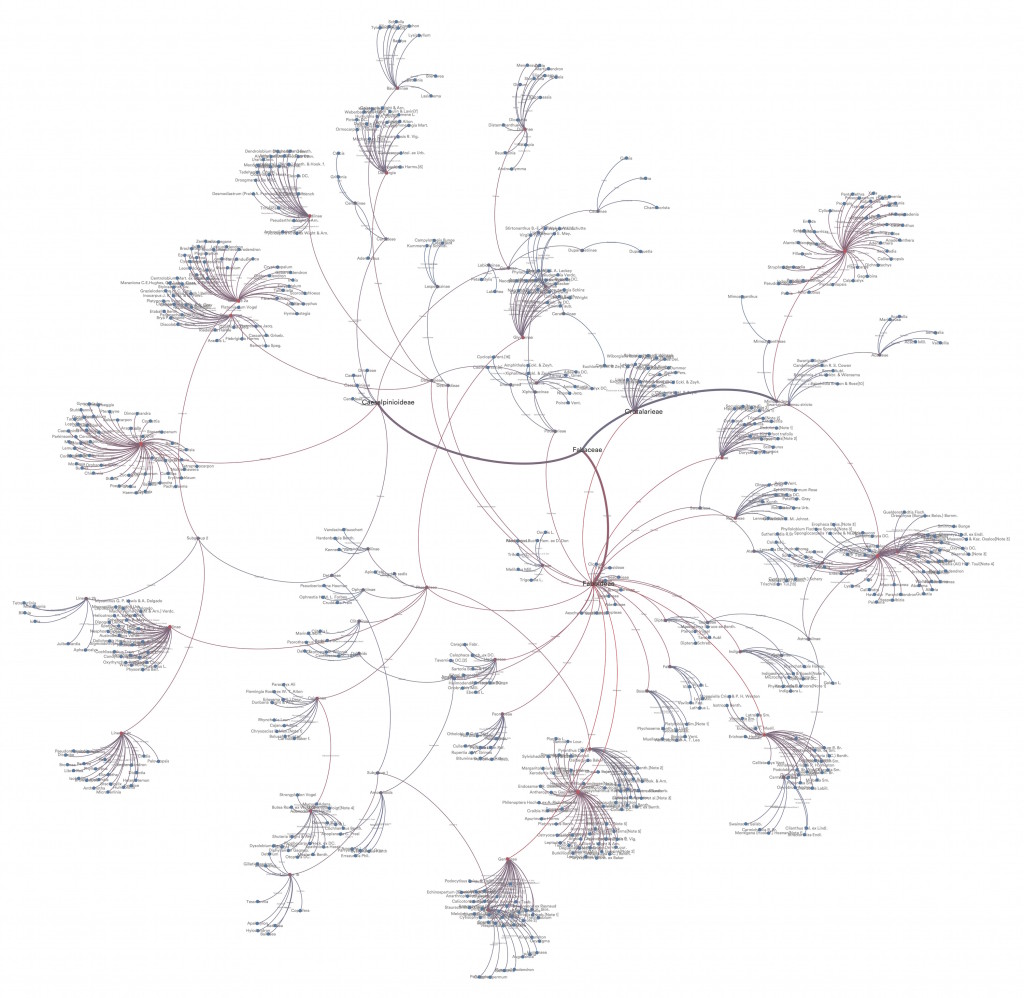

L.meridiani: Ecologically Viral Information

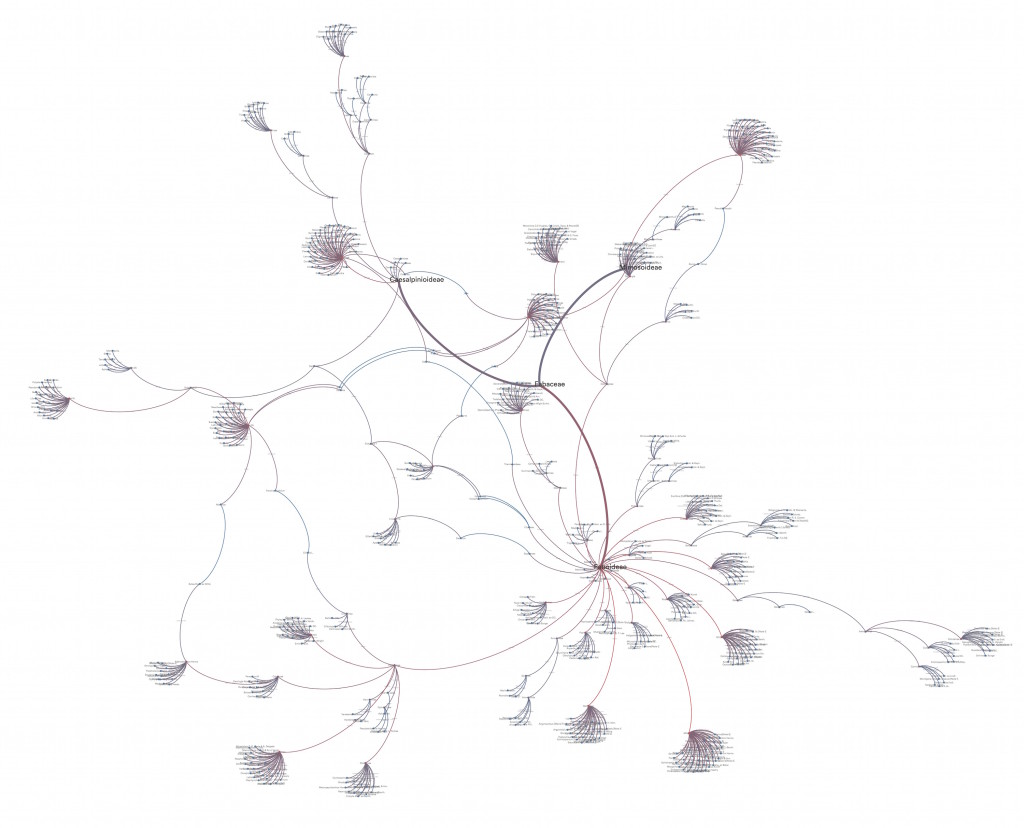

Scientific classification is usually portrayed in a family tree of hierarchy, or a cladogram. Once Lux took over cities, scientists found they needed a different approach to understanding the beetle and its ecological niche. They performed network analysis of the entire Fabaceae family of trees and the tree species that Lux colonized. Over time, they noticed that Lux’s virality was similar to the spread of information. When information spreads, it reshapes classification schemes and bridges previously unconnected groups. When information traverses an existing network, the underlying network itself changes. Similarly, Lux not only interacts with the Fabaceae network, but through ecological interaction, it also changes it.

Species that Lux touched would become morphologically similar to other, previously unrelated species in a more distant sub-tribe of Fabaceae. Lux was connecting and uniting formerly unconnected groups.

It was this function as a viral species between biological organism and information that led academics to deem Lux as “organic software”. With its own algorithms and logics that not only redefine the environment humans live in but create emergent feedback loops and system reclassifications, L. meridiani has irrevocably shifted our broader ecology in radical ways.